New York, NY (Top40 Charts) The

music industry, much like other sectors of the entertainment world, has to evolve continually. This can be down to technology as well as our entire cultural approach to enjoying the fruits of the labor of those who produce the output, and as a result, the models that these products are consumed and sold alter accordingly.

Whereas musical artists would see the bulk of their revenue accrued through the sale of physical music, be that from selling CDs, cassettes, or vinyl records, but the advent of the internet has pretty much slashed that stream of revenue.

Similarly, the coronavirus dealt a big blow to another stream of income, that made from live concerts. Though it's true things are starting to return to normality on that front, it's also true that it will take a while for this to return fully as it was.

This has led to artists, notably some big names in the industry, to develop new ways to secure significant uplifts in income, one of which relates to selling their entire back catalogs to the highest bidder.

This is partly down to the relatively low sums even the most prominent artists make from their music being placed on streaming services, and it's something we are likely to see a lot more of in the future.

Selling Their Life's Work

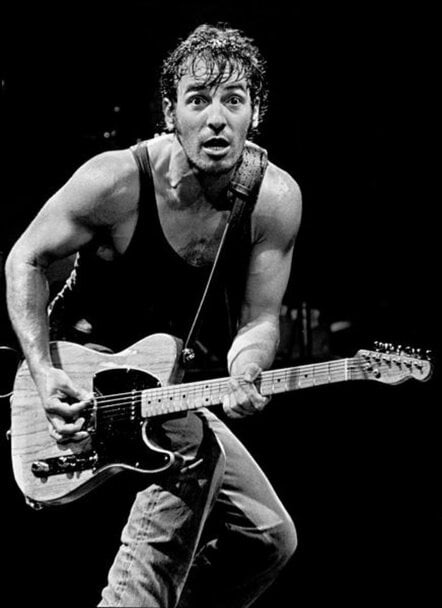

Among the big names choosing this option was Bruce Springsteen, who sold his entire back catalog to Sony Music Entertainment for a massive $550 million. This sum covers all the recorded work and the songwriting rights. This means Sony will be free to market the work of 'The Boss' in any way it chooses from now until they wish, or if they sell the rights later, transfer it accordingly.

In a way, it's the artists' way of securing a lump sum rather than counting on where the music world takes us next, and Springsteen isn't the only person to go down this route. Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Steve Nicks, Neil Young, and Shakira have done likewise, and it's an exciting development in the industry.

David Bowie's catalog was sold to Warner Chappell in a deal worth in excess of $250 million, a move that was met with effusive praise from its co-chair Carianne Marshall;

"This fantastic pact with the David Bowie estate opens up a universe of opportunities to take his extraordinary music into dynamic new places,"

"This isn't merely a catalog, but a living, breathing collection of timeless songs that are as powerful and resonant today as they were when they were first written."

And it's that sentiment that is particularly interesting. Owning an artist's entire catalog with such a rich history has a value that might be deemed almost priceless when considered in the long term. In this way, one can almost see the benefits to a buyer even more readily than to the artist whose work is being sold to the highest bidder.

There are some who speculate that the sums being paid by large companies are something of a 'bubble' and that it may not continue in the long-term, and it's undoubtedly a by-product of big artists seeing their massive tours curtailed.

Some have pointed out that those artists who are selling their catalogs, in the main, are those in advanced years and are selling off the asset as they plan their estates and know that holding such assets could result in considerable tax bills. So the act itself is a mixture of timing and convenience, albeit fueled by a differing approach to how the musical world generates a living for those who work within it.

Changing Musical Ecosystem

When it comes to making a living from music, it's worth looking at the other end of the spectrum rather than those megarich behemoths who are cashing in for a moment. A working musician now faces real challenges in trying to make even a modicum of revenue from their efforts.

However, the increase in popularity of royalty-free music and stock music has helped to provide some security for those who license their music to the relevant providers.

For those not familiar with royalty-free music, the industry provides large databases and libraries full of great music for use within social media or film and tv production, all for a subscription-based fee that negates the need for an additional cost and time of procuring additional licenses.

Basically, this gives users a rich resource of great musical output for a fraction of what it would cost to license established mainstream music and artists who offer their music for use by royalty-free music services, therefore, make a substantial sum from doing so.

It's true that the ever-changing musical landscape has left many within the industry, both at the top and bottom, struggling to secure a fair amount of money for their work, and therefore royalty-free music offers a steady alternative revenue stream for those who would otherwise more than likely make little or nothing from their endeavors.

For every Bruce Springsteen who sells his life's work for half a billion dollars, there are hundreds of others who struggle to get by, and this isn't helped by the fact that social media companies and streaming services fail to adequately pay for the use of music on their platforms, chiefly because they work with each other to keep their costs down.

While this means that listening and users get to enjoy the fruits of the work made by the talented musicians for next to nothing, somewhere down the line, the creator of the track (as well as the artists who play on it) are forgotten and forced to make do.

It's a system that is not sustainable, and we may well see musicians opting to take their music off these platforms (for reasons other than to do with a certain Joe Rogan) in order to secure a better deal for their work.